| LA MAISON DU BERGER (extrait) | from THE SHEPHERD’S HUT |

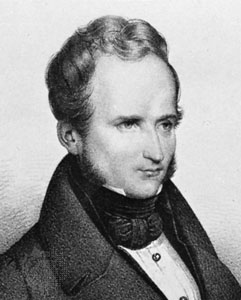

| Alfred de Vigny | trans. Stan Solomons |

| Elle me dit: “Je suis l’impassible théâtre Que ne peut remuer le pied de ses acteurs; Mes marches d’émeraude et mes parvis d’albâtre, Mes colonnes de marbre ont les dieux pour sculpteurs. Je n’entends ni vos cris ni vos soupirs; à peine Je sens passer sur moi la comédie humaine Qui cherche en vain au ciel ses muets spectateurs. “Je roule avec dédain, sans voir et sans entendre, A côté des fourmis les populations; Je ne distingue pas leur terrier de leur cendre, J’ignore en les portant les noms des nations. On me dit une mère et je suis une tombe. Mon hiver prend vos morts comme son hécatombe, Mon printemps ne sent pas vos adorations. ” Avant vous, j’étais belle et toujours parfumée, J’abandonnais au vent mes cheveux tout entiers: Je suivais dans les cieux ma route accoutumée, Sur l’axe harmonieux des divins balanciers. Après vous, traversant l’espace où tout s’élance, J’irai seule et sereine, en un chaste silence Je fendrai l’air du front et de mes seins altiers.” C’est là ce que me dit sa voix triste et superbe, Et dans mon coeur alors je la hais, et je vois Notre sang dans son onde et nos morts sous son herbe Nourrissant de leurs sucs la racine des bois. Et je dis â mes yeux qui lui trouvaient des charmes: “Ailleurs tous vos regards, ailleurs toutes vos larmes, Aimez ce que jamais on ne verra deux fois.” Oh! qui verra deux fois ta grâce et ta tendresse, Ange doux et plaintif qui parle en soupirant? Qui naîtra comme toi portant une caresse Dans chaque éclair tombe de ton regard mourant, Dans les balancements de ta tâte penchée, Dans ta taille indolente et mollement couchée, Et dans ton pur sourire amoureux et souffrant? Vivez, froide Nature, et revivez sans cesse Sous nos pieds, sur nos fronts, puisque c’est votre loi; Vivez et dédaignez, si vous êtes déesse, L’Homme, humble passager, qui dut vous être un Roi; Plus que tout votre règne et que les splendeurs vaines J’aime la majesté des souffrances humaines: Vous ne recevrez pas un cri d’amour de moi. | And Nature said: ” I am that theatre Insentient, unmoved by any actor. My emerald stairs, my courts of alabaster, My marble halls are sculpted by the Gods. Nought do I hear, nor cries or moans, And barely feel those that do play on me Scanning the silent sky for audience. Revolving with disdain and deaf to all, I cannot tell mankind from seething ants. Nor cannot tell their cities from their graves. I bear the nations’ names yet know them not. They call me Mother, and I am a Tomb. My winter claims a frozen holocaust, My spring impassive to your sacrifice. Before you came I was perfumed and fair My hair abandoned to the untamed breeze, I followed in the skies my fated orbit, Harmonious and predetermined way. When you have gone, ploughing through darting space, Serene and solitary, chaste and mute, Still will I cleave the sky with haughty brow. Thus sad and proud was Nature’s voice to me, And in my heart I hate her and I see Blood on her waves, our dead beneath the sward, Feeding the trees with all their dying juice. And yet I was bewitched by all her charms And said: ” Avert your gaze, dry up your tears, Love only that which passes and will die” Who will see twice your grace and tenderness, 0 my sweet love, and angel of my life? When shall I ever see your love again In the soft lightning of your suffering eyes, In the soft subtle bending of your head, And the soft outline of your willow form, And your pure smile of love and suffering. Live on, cold Nature, live on without end, Beneath us and above, since this is law, Live on, and if you’re God indeed, disdain Mere Man, a transient and yet your King. More than your realm and all your splendours vain, I love the majesty of human pain: You will receive no cry of love from me. |

Trans. copyright © Stan Solomons 2006

| LA MORT DU LOUP | THE DEATH OF THE WOLF |

| Alfred de Vigny | trans. Stan Solomons |

| I Les nuages couraient sur la lune enflammée Comme sur l’incendie on voit fuir la fumée, Et les bois étaient noirs jusques à l’horizon. Nous marchions, sans parler, dans l’humide gazon, Dans la bruyère épaisse et dans les hautes brandes, Lorsque, sous des sapins pareils à ceux des Landes, Nous avons aperçu les grands ongles marqués Par les loups voyageurs que nous avions traqués. Nous avons écouté, retenant notre haleine Et le pas suspendu. – Ni le bois ni la plaine Ne poussaient un soupir dans les airs; seulement La girouette en deuil criait au firmament; Car le vent, élevé bien au-dessus des terres, N’effleurait de ses pieds que les tours solitaires, Et les chênes d’en bas, contre les rocs penchés, Sur leurs coudes semblaient endormis et couchés Rien ne bruissait donc, lorsque, baissant la tête, Le plus vieux des chasseurs qui s’étaient mis en quête A regardé le sable en s’y couchant; bientôt, Lui que jamais ici l’on ne vit en défaut, A déclaré tout bas que ces marques récentes Annonçaient la démarche et les griffes puissantes De deux grands loups-cerviers et de deux louveteaux. Nous avons tous alors prépare nos couteaux, Et, cachant nos fusils et leurs lueurs trop blanches, Nous allions pas à pas en écartant les branches. Trois s’arrêtent, et moi, cherchant ce qu’ils voyaient, J’aperçois tout à coup deux yeux qui flamboyaient, Et je vois au-delà quatre formes légères Qui dansaient sous la lune au milieu des bruyères, Comme font chaque jour, à grand bruit sous nos yeux, Quand le maître revient, les lévriers joyeux. Leur forme était semblable, et semblable la danse; Mais les enfants du Loup se jouaient en silence, Sachant bien qu’à deux pas, ne dormant qu’à demi, Se couche dans ses murs l’homme, leur ennemi. Le père était debout, et plus loin, contre un arbre, Sa louve reposait comme celle de marbre Qu’adoraient les Romains, et dont les flancs velus Couvaient les demi-dieux Remus et Romulus. Le Loup vient et s’assied, les deux jambes dressées, Par leurs ongles crochus dans le sable enfoncées. Il s’est jugé perdu, puisqu’il était surpris, Sa retraite compté et tous ses chemins pris; Alors il a saisi, dans sa gueule brûlante, Du chien le plus hardi la gorge pantelante, Il n’a pas deserré ses mâchoires de fer, Malgré nos coups de feu qui traversaient sa chair, Et nos couteaux aigüs qui, comme des tenailles, Se croisaient en plongeant dans ses larges entrailles, Jusqu’au dernier moment où le chien étranglé, Mort longtemps avant lui, sous ses pieds a roulé. Le Loup le quitte alors et puis il nous regarde. Les couteaux lui restaient au flanc jusqu’à la garde, Le clouaient au gazon tout baigné dans son sang; Nos fusils l’entouraient en sinistre croissant. Il nous regarde encore, ensuite il se recouche, Tout en léchant le sang répandu sur sa bouche, Et, sans daigner savoir comment il a péri, Refermant ses grands yeux, meurt sans jeter un cri. II J’ai reposé mon front sur mon fusil sans poudre, Me prenant à penser, et n’ai pu me résoudre A poursuivre sa Louve et ses fils, qui, tous trois, Avaient voulu l’attendre, et, comme je le crois, Sans ses deux louveteaux, la belle et sombre veuve Ne l’eût pas laissé seul subir la grande épreuve; Mais son devoir était de les sauver, afin De pouvoir leur apprendre à bien souffrir la faim, A ne jamais entrer dans le pacte des villes Que l’homme a fait avec les animaux serviles Qui chassent devant lui, pour avoir le coucher, Les premiers possesseurs du bois et du rocher. III Hélas, ai-je pensé, malgré ce grand nom d’Hommes Que j’ai honte de nous, débiles que nous sommes! Comment on doit quitter la vie et tous ses maux, C’est vous qui le savez, sublimes animaux! A voir ce que l’on fut sur terre et ce qu’on laisse, Seul le silence est grand; tout le reste est faiblesse. Ah! je t’ai bien compris, sauvage voyageur, Et ton dernier regard m’est allé jusqu’au coeur! Il disait: “Si tu peux, fais que ton âme arrive, A force de rester studieuse et pensive, Jusqu’à ce haut degré de stoïque fierté Où, naissant dans les bois, j’ai tout d’abord monté. Gémir, pleurer, prier est également lâche Fais énergiquement ta longue et lourde tâche Dans la voie où la sort a voulu t’appeler, Puis après, comme moi, souffre et meurs sans parler.” | I The dark clouds sped across the orange moon As smoke trails streak across a fire And to the far horizon woods were black. Silent we walked amid the dewy grass, Amid dense briars and the vaulting heather Until beneath some moorland conifers We saw great gashes, marks of griping claws Made by the wandering wolves we tracked. We listened, holding back our breath, Stopped in mid-stride. Nor wood nor plain Loosed murmurs to the air, only The mourning wind-vane cried out to the sky For well above the ground the biting wind Only disturbed the solitary tower And the oaks within the shelter of the rocks On their gnarled elbows seemed to doze. No rustle then, but sudden, stooping low The most experienced hunter of our band Better to scrutinize the sand, Softly declared – and he was never wrong – That these fresh claw-marks showed without a doubt These were the very animals we sought, The two great wolves and their two stripling cubs. And then we all prepared our hunting knives, Hiding our guns and their fierce tell-tale gleam, We went on, step by step, parting the bushy screen. Three of us stopped, and, following their gaze, I noticed suddenly two eyes that blazed, And further off, two slender forms together, Dancing beneath the moon, amid the heather. And they were like the hounds that show their joy, Greeting their master with a wondrous noise. And they were like; like also was the dance Save that the cubs played all in silence, Knowing full well that near and sleeping slow, Secure inside his house was man their foe. The father wolf was up, further against a tree Remained his mate, a marble statue she, The same adored by Rome whose generous breast And suckling gave Remus and Romulus. The sire advanced with fore-legs braced to stand With cruel claws dug deeply in the sand. He was surprised and knew that he was lost For all the ways were seized, retreat cut off. Then, in his flaming maw, with one fell bound Seized the bare throat of our bravest hound. Like traps his steely jaws he would not leash, Despite our bullets searing through his flesh, And our keen knives like cruel and piercing nails, Clashing and plunging through his entrails. He held his grasp until the throttled hound, Dead long before, beneath his feet slumped down. The Wolf then let him drop and looked his fill At us. Our daggers thrust home to the hilt, Steeped in his blood impaled him to the ground, Our ring of rifles threaten and surround. He looked at us once more, while his blood spread Wide and far and his great life force ebbed Not deigning then to know how he had died Closed his great eyes, expired without a cry. II I couched my brow upon the smoking gun, And deep in thought, I tried to bend my mind To track the She-Wolf and her two young ones, They would most willingly have stayed behind. But for her cubs that fine and sombre mother Would not have left her mate there to endure, She had to save her children, nothing other, Teach them to suffer gladly pangs of hunger, Not sell their souls, enter that dishonourable Pact man forced upon those hapless beasts Who fawn and hunt for him, and do his will; The primal owners of the hills and forests. III Alas, I thought, despite the pride and name Of Man we are but feeble, fit for shame. The way to quit this life and all its ill You know the secret, sublime animal! See what of earthly life you can retain, Silence alone is noble – weakness remains. O traveller I understand you well, Your final gaze went to my very soul. Saying: “With all your being you must strive With strength and purpose and with all your thought To gain that high degree of stoic pride To which, although a beast I have aspired. Weeping or praying – all this is in vain. Shoulder your long and energetic task, The way that Destiny sees fit to ask, Then suffer and so die without complaint.” |

Trans. copyright © Stan Solomons 2006

Leave a Reply